The ‘Peace Psychologist’ in Kashmir Helping Women Affected by Conflict

May 28, 2019

Story

Ufra Mir is Kashmir’s first – and so far, only – ‘peace psychologist.’ In this strife-ridden region, she is trying to help women find peace in their lives and build it in theircommunities.

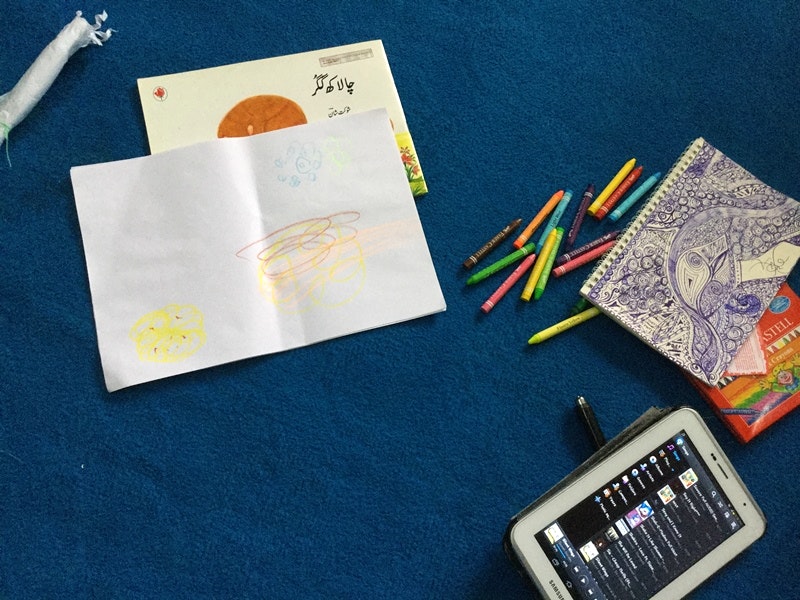

SRINAGAR, INDIAN-ADMINISTERED KASHMIR – With the light of the sinking sun seeping in through a plate-glass window, Ufra Mir leans over a spiral notebook on which she is doodling intricate designs. Dozens of Faber-Castell crayon colors – some old, some new – lie scattered on the floor of her office. She lifts her head as someone knocks on the half-open door.

With a broad smile, Mir, 29, greets a veiled woman, Amina Shiekh, 55, who hesitantly walks into the room. Shiekh lifts her veil; she looks tired.

Mir takes out a few sheets of blank paper, and hands them to Shiekh. Shiekh, a widow and a mother of three daughters, tells Mir she is dealing with a lot of “stress and hopelessness” in her life. Shiekh lost a son to cancer four years ago, and a husband to a heart attack two years ago.

Before he died, her husband’s ability to earn a livelihood as a carpet weaver had been affected by clashes in the disputed Kashmir region, which led to curfews and the frequent shutdown of all activity in the Kashmir Valley. When he died, Shiekh was left as the head of the household; she became a carpet weaver, too.

“I learned here that giving voice to the emotions lightens up one’s heart” The Himalayan region is beset with a territorial conflict between India and Pakistan that has been going on for seven decades. An estimated 70,000 people have died since the outbreak of an armed insurgency against Indian rule in 1990. And many men have simply disappeared, which has given birth to a new category of women known locally as “half-widows.” These women don’t know if their husbands are dead or alive.

Mir asks Shiekh to express her frustrations through a drawing, using any colors she wants. She chooses yellow and brown to draw abstract shapes. Mir interprets this image as the “chaos” and “clutter” in Shiekh’s life.

“It feels so good when someone listens to your problems carefully without judging you,” Shiekh says. “I learned here that giving voice to the emotions lightens up one’s heart.”

Before Shiekh leaves, Mir gives her some meditation exercises involving deep breathing to help control her stress and anger.

Mir is Kashmir’s first – and, so far, its only – “peace psychologist.” Peace psychology is a type of psychology that focuses on mitigating the effects of conflict on society and developing ways to promote peace. Mir’s personal brand of peace psychology includes talk therapy, art therapy and stress management techniques, but she also teaches leadership skills to ordinary people, and helps them analyze the conflict unfolding around them so that they can better cope with their environment.

“I believe that where there is pain, chaos and conflict, there is scope for art, creativity and the deepening of relationships, if only we can make that switch in our heads,” Mir says. “This is the reason I teach people how to express their trauma, stress and conflicts through creative expression.”

Mir, 29, was born in Srinagar, in the heart of the Kashmir Valley. When the armed insurgency against Indian rule broke out in 1990, her father’s restaurant business was badly hit and they had to move to Leh, more than 250 miles (400km) east. She moved back to Srinagar in high school, and went abroad for university, first to Luther College in the United States and then to the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom for her master’s degree. After completing her studies, she decided to use her newfound knowledge in her conflict-ridden homeland, where tens of thousands of people have been killed since the start of the armed insurgency.

“[Women] are fighting at micro and macro levels to ensure peace, whether it’s through small household chores or participating alongside men in peaceful protests.” Besides working as a counselor at a local private school, Mir also gives free sessions to women and youth from all over Kashmir, both individually – as in Shiekh’s case – and in groups, through her NGO Paigaam. Those she works with include at-risk youth; high school and college students who were injured by pellet shots last year during protests; and “half-widows.”

She says that she is trying to rekindle the confidence of Kashmir’s widows and “half-widows,” who often tell her they feel powerless and burdensome to their families.

“Women here […] don’t realize how through their patience, perseverance, compassion and empathy they are taking charge of their families, in the absence of a male head,” she says. “Mothers are catering to the daily needs of their children and doing everything to keep them safe. They are fighting at micro and macro levels to ensure peace, whether it’s through small household chores or participating alongside men in peaceful protests on the streets.”

Mir says she tries to open their eyes to their own resilience: “When there is so much turmoil around, women mostly take their small steps of courage for granted, and this lowers their self-esteem,” she says.

Mir says she also sees many women who seem disconnected from the present, with thoughts focused on past losses.

“It is not bad to acknowledge the sense of loss,” she said. “But I have seen these women limiting their understanding of peace to some sort of constant future goal without trying to cope with what is happening, leaving these women more stressed and helpless.”

“Women in Kashmir are trying to change things in extraordinary circumstances, where they could have lived their entire lives as victims.” Mir frequently represents the Kashmir region at various national and international forums on mental health and leadership development. She is currently working with a New Delhi-based organization on leadership development for educational officials working throughout Kashmir. The end goal is to improve student learning outcomes in a region where schools are frequently affected by general shutdowns.

Barba Aijaz, a student who has worked with Mir, says she is a “peacemaker.” She says doing meditation exercises and art therapy – and, at Mir’s prodding, keeping a daily journal of events – has helped her enormously over the past five years.

“Writing has helped me fight with everyday stressors and put all the good and bad feelings on paper,” she says. “I’ve learned that what’s more important is to know how to channelize and express one’s emotions in a healthy way, without harming yourself.”

Mir feels her work is particularly relevant at a time when the conflict is gearing up again, with frequent clashes and shutdowns.

“In peace-building, trust is important,” she says. And women’s trust in themselves is key to creating lasting peace: “Women in Kashmir are trying to change things in extraordinary circumstances, where they could have lived their entire lives as victims.”

....Ends...

Courtesy: (https://www.newsdeeply.com/womenandgirls/articles/2017/08/15/the-peace-p...)

How to Get Involved

Mir: "Women, I believe, are at the forefront of pain and conflict anywhere and everywhere. And yet, if you choose to change the narrative of your life, by choosing to not just survive but also be a conscious agent of positive change and resilience as a woman peacebuilder, you tend to face way more challenges [than men].

“The most common one, based on my experience, is cold reception in the field due to gender stereotyping and bias. Women are seen as peacebuilders in family disputes but not in the outer world. Men tend to think that the space for analysis, policymaking and intellectualism, all of which is important to peacemaking and building, somehow should be better occupied by their own.

Additionally, I believe women peacebuilders end up doing more than they should be doing sometimes because of their duties for their families, running households, earning an income and also trying to build peace out there. It is physically and emotionally straining, to say the least. On the other hand, I think women sometimes tend to underestimate their inner strength and power, again due to societal pressures and stereotypes, which stops them from seeing themselves as good empathetic leaders because power is perceived as something ‘bad.’

Spreading awareness about the field itself and the importance of the place for women in it; showcasing and highlighting stories of women peacebuilders from around the world; encouraging women peacebuilders through awards, fellowships, invitations to international conferences and U.N. forums so that more people understand how ordinary women are doing extraordinary things; leadership programs for women peacebuilders; building a strong network for women peacebuilders in connection with male peacebuilders; and maybe having male peacebuilders support women peacebuilders in their countries to help get rid of gender stereotypes and bias."