Women and Girls and Popular Education 2013 VOF Week 3

Nov 21, 2018

Story

bell hooks says, “. . . the purpose of education is to show students how to define themselves . . . in the world”

Women’s potentially distinctive learning characteristics have been a topic of interest to scholars, educators, and women. Historically, our ability to learn has been questioned by male Western philosophers and the value of education for women deemed less important than their reproductive capacities.

Paulo Freire’s theory of popular education may provide insight into the ways that women and girls might enhance and transform their world with three goals:

1. Popular education is aimed at empowering the participants through reflection and action

2. Popular education is political education

3. Popular education is the education of the people who are excluded or marginalized by dominant society

Popular education’s key principles include: everyone teaches and learns; everyone shares leadership; education is based on the learner’s experiences and concerns; everyone participates on all levels; students produce new knowledge; students implement critical reflection; students connect local issues to global issues; and, all participate in collective action for social change.

Efforts to incorporate women’s and girls’ knowledge and experience into the learning process may result in a deeper awareness of the sociocultural reality that shapes their lives. Some women/girls seeking education have wondered if there might be a different way to learn that resonates with the experience of being female. Popular education may be an effective vehicle to promote this learning environment.

Popular education philosophy can encourage understanding of the standpoint of being a girl/woman living in today’s world. In this way, they look critically at power structures from their gender and recognize forms of oppression such as poverty, racism, sexism, and class. A focus on gender recognizes the differences between men/boys and women/girls in relation to division of household labor as well as access to and control over resources, assets, and education. It is important to analyze the simultaneous experience of both privilege and marginality in order to identify the multiplicity of oppressions of ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, differently abled, language, and geographical location that originate in and support a masculinist/male dominant society.

Popular education enabled homeless mothers in the Boston area to attain their high school GEDs. The women intended to increase their self-esteem, to become inspired to help other low-income women, to advocate for their rights, and to become more involved in their children’s education. The women used knowledge and expertise they gained from popular education to circulate petitions, write letters to legislators, organize and attend lobby days at their state capitol, speak at rallies, and develop pertinent handout materials for information booths at local health fairs. The women created new knowledge and shared this with their community through action for social change, to address the academic, personal, and community goals of the poor women and challenge their culture of silence and hopelessness. This helped them remove barriers and move beyond the social and cultural expectations for poor, single mothers. They definitely transgressed the boundaries that held them down and out. The women created action that impacted their community, based on their knowledge of their lived experience of being a poor, homeless, uneducated woman-mother. They transgressed their oppression, mandated by a male dominant society, creating a new vision for and of them.

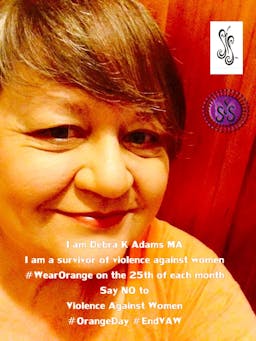

Another excellent demonstration of the positive impact of popular education for women is a writing project in Australia that was facilitated for the benefit of guiding women through the traumatic life situation of domestic violence. The women used written words and drawing to communicate their experiences. Using creative writing, journaling, drawing, painting, and making artwork of all genres, the women were able to name their world through their words and images. The women questioned the language used by the professionals surrounding them and remade that language into a description of their actual experiences. They investigated the power structure of the violence from the inside out and controlled the re-telling of their stories, through their art, embodying their emotional truths by remaking the language to discover fundamental knowledge of their lives. The praxis of empowerment for the women came as a result of not accepting the use of language as it was given to them - they subverted the domination of the abuser/oppressors and gained emotional and physical freedom for themselves.

We must, as a society, look for ways improve access to education for women and girls, to be more inclusive of multiple identities and standpoints, creating safe space within classrooms for the expression of all students’ voices and for the transformative experience of a liberatory education for all.