Examining the Effectiveness of Sexual Violence Prevention Programming

May 28, 2019

Story

As a member of a small group of students tasked with designing and implementing Portland State University's Sexual Violence Prevention and Advocacy program, I've begun to examine best practices for sexual violence prevention. This includes the study and analysis of writings from a diversity of sources and experiences including, men, women, survivors, perpetrators, experts, and bloggers.

This week I worked with a chapter from Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Power & A World Without Rape entitled Hooking Up with Healthy Sexuality: The lessons Boys Learn (and don’t learn) About Sexuality and Why a Sex Positive Rape Prevention Paradigm Can Benefit Everyone Involved. This piece really helped me find fusion between sexual health promotion, and sexual violence prevention. The author explains how the movement to address rape culture typically separates sexual health promotion and sexual violence prevention, and strategizes for them individually. Creating some programming to promote healthy sexuality over here, and creating programming to prevent sexual violence over there. However, a more effective strategy would be to start thinking of sexual health promotion as sexual violence prevention in and of itself. The author offers that “Understanding how boys are socialized to view sexuality can show us where to blend the approaches of sexual violence preventions and sexual health promotion, and how to enhance the effectiveness of programs rooted in these fields. But first we have to pull back the curtain on our unhealthy sexual status quo.”

With this in mind, I began to think about the college campus environment and culture, and how sexual violence prevention might shift to look more like sexual health promotion. This lead to rethinking the Chiron Studies course that I have been developing. Everything from the title to the content has been more concentrated in helping students understand the trauma of gendered violence, and the damaging impacts of rape culture on our emotional and mental health. The end goal being to prevent sexual violence. However, as I chewed on this reading, and incorporated our in group discussions on prevention, I began to think that a more effective strategy might be to code these concepts into language and curriculum that even those who fit the perpetrator norm would be excited to engage with. I thought about how much college students love to talk about sex. How courses with the word “sex” or “sexuality” embedded in their title, are so often full to capacity, with a full wait list as well. I thought about how as a student taught class, Chiron courses offer preventionist programming a platform to utilize peer relationships, and offer legitimacy. I thought about how as a level 100 course, it might offer access to incoming students who are most vulnerable. It occurred to me that a course entitled Radical Sex Ed 101: Sexual Pleasure and Sexy Consent, might enroll a broader base than a course entitled, Rape Culture: How Misogyny Makes Us Sick.

Really, this would be leveraging the existing pop culture of sexiness, rather than critiquing it or arguing against it. Regardless of how I might personally feel about our hypersexualized culture, it exists. The goal, then, would be to market consent as sexy, in an effort to normalize consent. While the effort to make consent sexy is not a new idea, leveraging it and even embedding it in sexual violence prevention programming is a relatively new strategy. The ‘Consent Is Sexy’ campaign has gained some momentum in the last couple of years, with posters and memes making their way onto high school and college campuses across the nation. Of course there are, as always, critiques of this strategy. In a recent piece from HuffPost College entitled “Does UCSC's 'Consent Is Sexy' Campaign Miss The Point?”, a male student at UC Santa Cruz critiqued that:

“Consent is a mandatory thing, and I think it's important to raise awareness about consent, but not necessarily in this context of it's sexy or trendy, but rather the serious nature of the fact that … consent is mandatory," Holger said. "I think a campaign that even has the slogan 'consent is mandatory' would be just as effective, if not more effective."

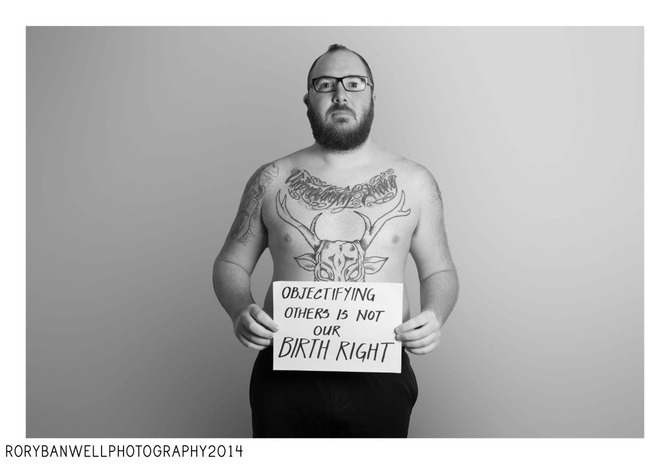

This is a valid critique. Consent is not optional. Consent is about more than just a sexy meme or a hip trend. It is mandatory. It is a human rights issue. But can consent be sexy and mandatory. Can we go even further and can consent become normalized? Can we build and nourish a culture in which all humans are supported in developing healthy sexuality, making consent as much a part of sexual activity as the physical aspects are? These are big questions that I want to collectively answer, and I think that it is also important to never ever lose sight of the fact that sexual violence is an exercise of power and social control over women’s bodies. While it is absolutely true that the lack of healthy sexual development contributes to the occurrence of rape, the root of the issue is and has always been about the display of male power and social control.

Back in 2000, Luoluo Hong’s essay entitled” Toward a Transformed Approach to Prevention: Breaking the Link Between Masculinity and Violence” , she argued that there is an undeniable and documented link between “socialization into stereotypical norms of hegemonic masculinity”, and sexual violence. Hong supports the growing community of researchers and writers who assert that “...the predominate male socialization process in the United States inculcates in boys and men a hegemonic and limiting code of masculinity that intimately links traditional male gender roles with violence and, therefore, may predispose men to be perpetrators and victims of violence.” Here I appreciate the acknowledgement that yes, men can also be victimized, but that perpetrators of violence against men, are men themselves, and that we must not fail to consider the gender-related nature of violence.Hong also discusses the importance of “...expanding male students’ conceptions of manhood and appropriate gender roles and, thus, reducing the likelihood of men’s engaging in sexually or physically violent behavior.”

My question is then, if sexual violence, at its root, is about exertion of power and control, and boys men are impositionally socialized to assert power and control, is leveraging the ‘Consent is Sexy’ campaign an effective strategy for not only fostering a culture of healthy sexuality in which rape is inconsistent with the social norms, but for creating an opportunity for men to redefine masculinity altogether?

*Men can stop rape. http://www.mencanstoprape.org

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zx8hG6JeADk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KTvSfeCRxe8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dRuPFmo15Tk

Sources and Citations

Friedman, Jaclyn, and Jessica Valenti. "Hooking Up with Healthy Sexuality: The Lessons Boys Learn (and Don’t Learn) About Sexuality and Why a Sex Positive Rape Prevention Paradigm Can Benefit Everyone Involved." Yes Means Yes!: Visions of Female Sexual Power & a World without Rape.

Gabreyes, Rahel. "Does UCSC's 'Consent Is Sexy' Campaign Miss The Point?" HuffPost College. N.p., 16 Nov. 2015. Web. 11 Feb. 2016. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/ucsc-consent-is-sexy-campaign_us_564...

Hong, Luoluo, PhD, MPH. "Toward a Transformed Approach to Prevention: Breaking the Link Between Masculinity and Violence." (2000)