Born to fail? Selling education to the chronically poor

Jan 21, 2015

Story

By the time she turned fifteen, Shameka had had five lovers. Her latest suitor, Gregory, is 62, wealthy, married, and deeply connected in the local political landscape. A long-time family friend, Gregory is considered a godsend shouldering much of the financial burdens of Shameka's schooling, even contributing the much-needed weekly lunch monies and bus fares for her four younger siblings.

In the inner-city community where Shameka resides, Gregory is respected for his wealth and connections, and this collective deference is automatically passed on to Shameka and her family. The relationship has elevated her status in the community, making her worthy of respect in an environment where money is an elusive commodity and the most common ways to acquire it is either through dealing drugs, selling sex, offering political favours, or getting involved in criminal activity.

Precious, Shameka's mother, is proud of her daughter who has not only passed her GSAT exams to enter one of the top high schools in Kingston, but has done well in attracting a man of Gregory's prestige. A single mother with five children, she is relieved to be getting some sort of financial support given that the minimum wages she earns as a domestic helper is barely enough to find food for her children.

Precious remembers when, barely past Shameka's age, she got pregnant for the first time and had to drop out of school. She regrets that Shameka's father, Teddy, a boy from her community denied fathering the child which meant she had to raise Shameka all by herself. She sometimes wishes that Shameka's father, who was killed by the police in a robbery attempt six years ago, was around to witness how well his daughter has turned out.

She worries about the future of her children, but feels confident that with Gregory's assistance Shameka will be able to complete her schooling and eventually move out of the community. She cautions Shameka against getting pregnant as that would mean she would be expelled from school, but at the same time, she is glad that Gregory has the financial means to be able to provide for the child.

A Familiar Tale: Chronic Poverty as a Barrier to Education

Sadly, Shameka's story is not uncommon in many poor communities in Jamaica. Young girls like Shameka who are born and bred into a perpetual cycle of poverty are often robbed of their youths as they are thrust, often from as early as nine or ten years old, into positions of responsibility, fending for themselves and their families.

Whilst it is generally accepted that investing in education is one of the most effective ways to reduce poverty, this understanding hasn't necessarily resonated within the mindsets of some of the poorest citizens who are generally exploited by a system that forces them to barter themselves or their children in an effort to survive. The general moral values of society ultimately become insufficient to combat the gripping tentacles of poverty where in many cases, children and especially girls become victims of circumstance.

Chronic poverty undermines the abilities of families to place sufficient emphasis on education, in a system where education, in practice, remains a commodity. Prohibitive tuition fees, high costs of textbooks and schools supplies, daily lunch monies, and bus fares or other transportation fees, make education a secondary priority for many parents who are struggling to find food and shelter for themselves and their children. Inspite of the general wisdom that the education of girls has a far-reaching impact in reducing inter-generational poverty, a girl's education is often readily sacrificed in the pursuit of economic gain.

Recognizing the Value of an Educated Girl:

For developing countries like Jamaica, the challenge remains not only to promote the education of girls as the most viable means to escape poverty, but to significantly reduce the barriers to acquiring an education especially for families which are at or below the poverty line. The challenge remains to annihilate the myths and misconceptions that girls are commodities to be bartered in exchange for financial or other gain.

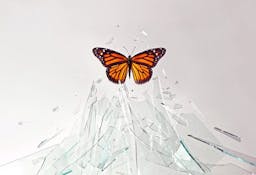

An educated girl is better able to provide for her family in the long-run, to participate and make greater contributions to the labour force, and to plan and better prepare for child-rearing than one who is not. The contributions of an educated girl to sustainable development is critical and invaluable. Girls like Shameka have the promise and the ability to escape the grip of poverty and to wrest from the exploitative tentacles of those who will stunt her growth.

Interventions at the school and community levels are necessary to empower such girls, women, and their families to recognize the incalculable value that girls have. Moreover, an adequate legislative framework is needed to protect young girls from predatory adults who aim to exploit their vulnerabilities.