No place to Hide! Repression, Activism and Shrinking Civic Spaces

Aug 30, 2020

Story

Africa and the world at large is replete with examples of state sponsored repression on human rights defenders or those who speak out against various forms of social injustices ranging from land grabs, corruption, bad governance, exploitation of workers, natural resources looting, women rights violation, extra judicial killings of young people among other unfair practices. These range for example from bloggers arrests in Kenya, to shooting at workers demanding fair wages in South Africa, to mass incarceration of demonstrators in Ethiopia, to sexual violence against women street protestors in Egypt, to linguistic suppression in Cameroon, to the Internet shut down during Uganda’s general election, to the Ethiopian online blackout and abuse of human rights defenders who speak out against oil in Uganda and Kenya and the murder of Ethiopian music icon originating from the Oromo community[1]

As noted by Oxfam [1] spaces for civic engagement is closing in both autocratic and seemingly democratic states that have traditionally supported freedom of expression. The major reasons for fear of civic activism are to prevent dissent and other forms of popular uprising. Mass surveillance strategies are being employed to monitor both public and private spheres of human rights and social justice activists.

Restrictions on civil society and activism became more prominent with the international efforts to improve foreign aid. Many governments to imply host government ownership misinterpreted the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the incorporating of concepts such as host country ownership. This resulted into introduction of restrictive measures regarding international funding. According to the International Centre for Non Profit Law (ICNL) between 2004- 2010 over 50 countries considered or enacted measures restricting civil society

Various forms of oppression are currently being employed across the continent. These as noted by Rutzen (2015) [2] include stigmatisation of activists as ‘anti-state’, anti-religious, ‘agents of western powers’, members of armed opposition groups, sex workers, traffickers, ‘corrupt entities embezzling donor funding’. Systems are then put in place to curtail the movement and operation of activists include interference with travel, writing or association with others. This can be interpreted to view civil society as agents of foreign government hence deliberately squashed by the state apparatus.

The judiciary is an arm of government and in an ideal situation there ought to exist separation of powers. Justice had three attributes namely a blindfold, a balance and a sword. The blindfold represented objectivity, sometimes she is portrayed holding a flame or torch in one hand symbolising truth. The judiciary has sometimes not been true to its calling of dispensing justice more so in instances when it involved activists .For example in Kenya in 2013, 17 activists protesting against pay hike by Members of Parliament were arraigned in court and accused of taking part in a riot, breach of peace and cruelty to animals.[15].The other side of the coin is that the MPs were raising their salaries a burden borne by Kenyans’ mostly the poor who are the majority through heavy taxation and rising rates of inflation. The question that seeks an answer is whose interest should be a priority, is it the MPs who already access have access to basic necessities and are leading a comfortable life or poor Kenyans who are not sure where the next meal will come from. In Cameroon, activist Nasako Besingi got convicted on four criminal counts against the America palm oil company Herakles Farms. Besingi is the director of the Cameroonian NGOS Struggle to Economize our Future Environment (SEFE), SEFE’s activism against palm oil plantations and the negative impact they are having on the environment. Besingi’s charges include defamation and propagation of false news against the US agribusiness company. His court case took 3 years and he was sentenced to pay a fine of $2,400 or face up to three years in prison.

Activists cannot operate freely when they are under the radar of the state. When under state monitor, what the activists do, what they say and what they write, where they do is all documented. Many a times they are called to police stations to record statements and their houses can be subjected to raids. The summoning of 17 human rights workers in Egypt among them Mozn Hassan of Nazra for Feminist Studies and the arrest of Dr. Stella Nyanzi due to her Facebook posts is an example of being under state radar.

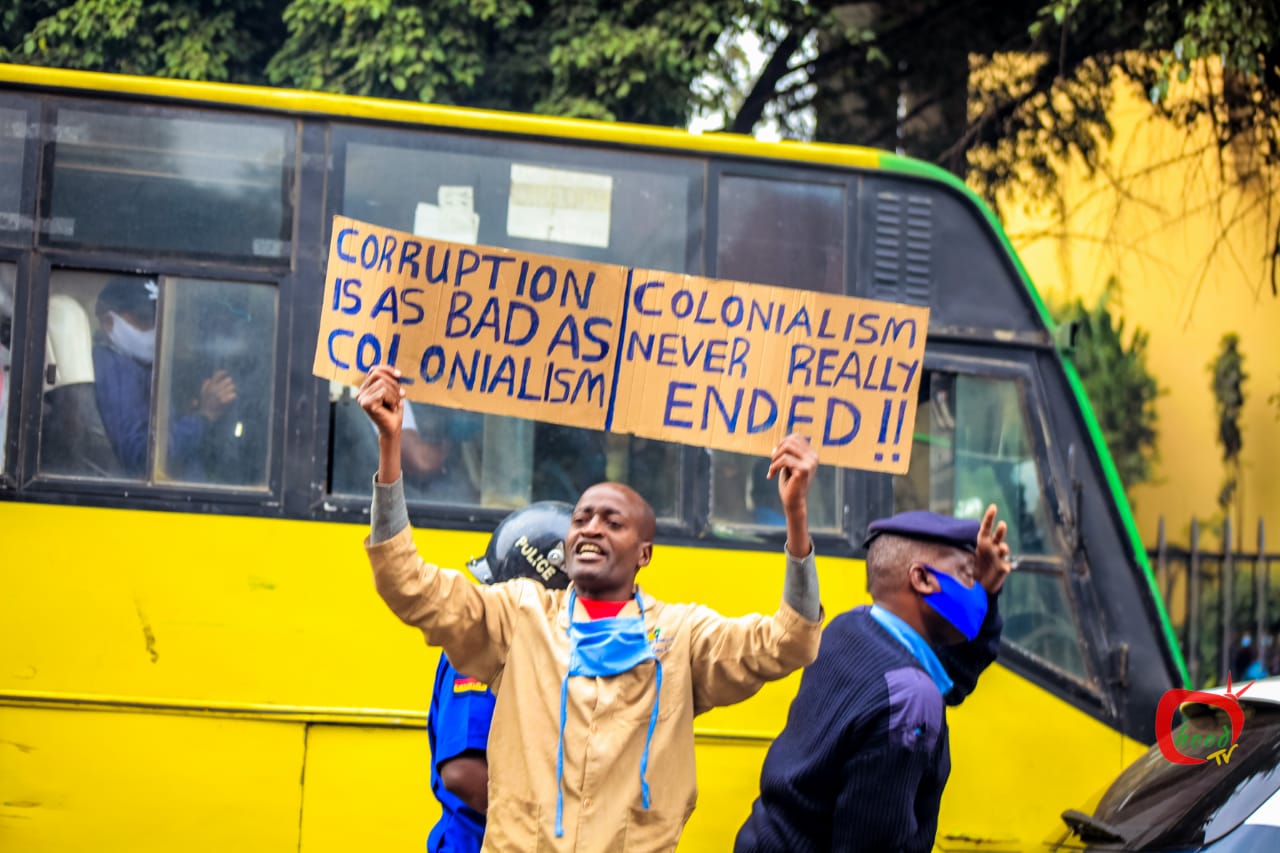

Others forms of state repression include blackmail, sent either through phone calls or text messaging. Kenya has various examples where civil society organisations have either been accused of being sympathetic to terrorists through funding their activities [4]. Additionally, the repressive arm of government has many a times offered a blind eye to the good work done by civil society, from providing medical care to regions which do not have medical access, to education services to children who would otherwise never know how to read and write, to humanitarian support in times of tragedy such as floods and famine. A more recent example in Kenya during the Covid 19 period is the arrest of activists[2] during Saba Saba March for Our lives demonstration which had been scheduled for the Nairobi’s Central Business district.

There have been instances where Kenyan government has put up a list of organisations at risk of being de-registered, being accused of various malpractices such as misappropriation and embezzlement of donor funds, diversion of donor funds, money laundering and terrorism financing [5]. This is all in a bid to frustrate active civic engagement while at the same time silencing voices deemed vocal on issues of human rights and social justice. The introduction of new pieces of legislation has also contributed to the continuing litany of civil society woes at the hands of government. Under addressing internal and external security issues, states such as Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania have enacted Anti Terrorism laws. These laws in some instances repress a section of community belonging to the Islam faith. In many cases there has been mass arrests of communities under security operations only for the victims to voice incidences of intimidation, torture, and in some cases being released after relatives have parted with huge sums of money.

Other attacks on activists by states have included being put under stringent administrative measures such as being frustrated with renewal of civil society registration certificate, being forced to divulge financial sources, raids on computer hardware’s to find out what information an organization had , such as the Egyptian raid on rights groups, smear campaign against activists leading to loss of livelihoods, family and community hostility among other forms of deliberate isolationist tendencies meted on activists to make them look bad in the eyes of the communities they serve and lose honour in the eyes of their immediate family members. There are instances where activists get physically attacked, injured and even killed in the process. Incidences of such include crack down on activists in Burundi resulted to deaths and disappearance of activists [7]. Furthermore, the government banned live reporting from sites of demonstrations by radio stations such as Radio Publique africaine(RPA), Radio Isanganiro and Radio Bonesha including cutting off telephone lines. For both activists and civilians arrested the reasons for arrests were mainly participating in illegal protests as well as speaking out against the government. Pierre Claver Mbonimpa a Burundian human rights defender was arrested for being an outspoken critic of abuses by the government.

Artists are not spared in state perpetrated crackdown, they are deemed as raising community consciousness, which should be silenced forever. Through graffiti, spoken word and progressive music, artists speak out against injustices in communities. From corruption to insecurity, rising poverty levels to mass unemployment of youths, to gender based violence and laxity in response to issues raised by communities. Incidences of state repression on artists has been evident in Burundi resulting into some artists having to flee the country and seek political asylum elsewhere especially after the Third Term Debate. In Tanzania, artists who criticise the government have had it rough, such include Vitali Maembe who speaks out against corruption, bad governance among other vices in Tanzanian society and in Africa has faced police arrests and brutality because of his songs [8]. For many governments in Africa are keen to keep communities intimidated and silenced and any attempts to change this imbalanced setting is resisted with a lot of vengeance.

Radio stations and journalist also get the wrath of the state, when they report cases that are deemed to undermine the state and governance processes. Talking about a faulted election, poor service provision, corruption by state officials can get you a jail term of a hefty fine. In extreme cases defending the rights of the poor against a police officer who has the power of the gun, can send you to an early graveyard. Such was the case of Kenya’s human rights lawyer Willie Kimani, taxi driver Joseph Muiruri and their client Josphat Mwende who were abducted on their way to court and later found killed and dumped in Ol-Donyo Sabuk, Eastern region of Kenyan. Kenyans led by the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) together with social justice activists took to the streets with nationwide protest; the matter is currently in court. [9] In Tanzania Amnesty International cites cases of rights abuse against people speaking out on injustice. Such include the arrest and charging of journalists under Cap 16 of Tanzania’s Penal Code, Cyber Crimes Act 2015 and the Newspaper Act of 1976 (mark the year 1976).

Radio stations are also silenced when reporters get arrested, warned and intimidated. Such include Radio Five and Magic FM which were closed for airing seditious content, as well as people getting charged under the Cybercrime Act for posting about the turn of elections and the president on Facebook. Furthermore, in Kenya, there was a lot of anxiety with the impending tapping of mobile phones to root out hate speech given that 2017 is the general election year, [10]. This this was contested in court by Okiya Omtatah who petitioned High Court to stop the Communications Authority from spying on mobile phones citing this as illegal and a violation of the public right to privacy.

Journalists and bloggers have been arrested in different countries for what they write and what they publish. For example in Ethiopia in 2014 the government arrested 6 members of the Zone 9 bloggers and 3 other journalists, whereas in Somalia, journalist have gotten arrested and questioned by the National Intelligence and Security Agency and have gone to be accused of trying to leave the country with a ‘one-sided story’. [11]. In July 2020, a Kenyan freelance journalist Yasin Juma was arrested in Ethiopia while covering protests in Oromia region of Ethiopia after the death of musician Huchalu Hundesa[3].To arrest a journalist, a blogger is to deny people the right to information of which many African states have enshrined within the constitutions.

The state makes use of various ways to intimidate activists, humiliate them, police, punish, silence as well as deter would be activists from speaking out or engaging in any form of protest. States are making use of technology to monitor those engaged in social justice work. This ranges from the insistence and collusion with Internet Service Providers (ISPs) that the clients using the services must register their sim cards. This is factored in under the guise of promoting security and preventing misuse of communication gadgets. In Ethiopia for instance in 5th -7th August 2016 in Amhara and Oromia regions, 100 people were killed by state security forces during peaceful protests for land rights, indigenous rights and good governance [12]. Furthermore, as Yared Hailemariam an Ethiopian activist told Frontline Defenders, journalists, protest leaders and rights activists have been followed and threatened using phone calls and emails for their role in mobilising civil society.

Countries have Access to Information law as part of human rights provisions for its citizens. Such include the Access to Information Act (2016) in Kenya. It ought to be noted that access to information and freedom of expression go hand in hand. State monitoring especially of activists is on the increase. Despite being initially viewed as a tool for combating crime, this software has been abused in various setting such as monitoring of law firms, journalists, activists and opposition political leaders in a country such as Bahrain [13].

Within the Kenyan context, state repression by use of media is being experienced. For instance, Article 19 East Africa documented from January to September 2015, over 60 journalists and bloggers were silenced, intimidated, harassed and some even killed in a spate of violence against freedom of expression, freedom of the media and access to information. This silencing has been by police, state officials, politicians and other individuals in power. Legislations have also been introduced in a bid to repress freedom of expression. On one hand bloggers who speak out against social evils such as corruption get arrested and the same courts find politicians who are use hate speech not to have cases to answer.

Using Section 29 of the Information and Communications Act in Kenya, Kenyans using online spaces have not been spared from repressive forces. This is presented as ‘improper use of licensed telecommunication gadget”. Furthermore, there has been charges such as “undermining the authority of a public officer “for criticizing government officials on social media which is in Section 132 of the Penal Code (Chapter 63 of the Laws of Kenya), Robert Alai has been charged under this section. Arrests on flimsy charges such as taking photographs deemed to be inappropriate or showing an element of inefficiency has also been a bid to silence people from speaking out. For instance, Ezer Kirui got arrested in 2016 for taking a photo of a long queue at a Huduma[4] Centre in Nakuru.A Huduma Centre is a government centre providing services to the public such as single business permits, search and registration of business names, student loan applications among other services. In an ideal situation the Huduma Centre is supposed to be efficient. Kirui wanted to share online how the services at the centre are slow, an arrest was done despite Huduma Centres not being gazetted as areas under Protected Areas Act within the Kenyan context. With the slow wheel of justice in the Kenyan context comprising of adjournments and never ending mentions, access to justice for activists becomes a mirage and cases may drag on for years with innumerable trips to the courts.

Resources are an integral part of activism. To organise people resources are needed however the glaring reality is that access to resources is also being used as an avenue for oppressing activism under the guise of financial accountability and transparency on donor funding. The state is the main duty bearer and is the one mandated to provide the services to be people, civil society only come in to complement. Various restrictions have evolved as far as issues of funding for activism and civil society work is concerned. Such include capping the amount of funding CSOs should receive [12. This it can be concluded is a presumption that the more money an NGO gets from foreign sources, the more the NGO is pushing the agenda of external forces.

In South Africa, the Marikana workers were met with shooting by police, their crime? Demanding right to decent wages. This shows to what extent government can protect multinational corporations at the expense of their own nationals, to date, the worker’s demands are yet to be met, while the company –Lonmin Mine continues to make millions of dollars. The contradiction is that where the miners live is one of the poorest areas of South Africa while the number of minerals extracted from the locality fetches billions in the world market. In Uganda, activists continue to be harassed for the work they do, this range from protecting the rights of minorities, to those working on land and extractives to those working on women rights. Additionally, the during the 2016 Presidential and parliamentary elections, over 170 journalists and political activists were facing intimidation and threats from governments institutions including the police and the district commissioners [14]. This repression is aimed at silencing dissenting views and towing the line of the ruling party.

The academic domain has time and again encountered state repression through arrests of academia and detentions, for instance the peak in Kenya was the 1990s when academic could be arrested and detained without trial, In Uganda, academia Dr. Stella Nyanzi was held at the Luzira Maximum prison and been denied bail because she has been vocal about the government’s failure to fulfil its commitment in provision of sanitary pads to all school girls, this despite being a campaign promise before the 2016 elections.

People protesting for social justice have faced brutal repression across Africa. Their crime, speaking out against the social wrongs in society or critiquing the government of the day. In Ethiopia, the Oromo protested against their land being taken away and were meted with mass incarcerations, internet shutdown and mass abuse, there were confirmed detention in areas such as Aris (670 people) and Wollega (110 people), in Sebeta over 1000 people were arrested in Sebeta near Addis. There was also death of 700 people [15].

It is worth concluding that with state repression, activists the world over have been forced to device new ways of operating and new strategies of survival. Repression has become a global trend and requires global concerted effort. And with the emergence of Covid 19 Pandemic, repression continues under the guise of ensuring citizen adherence to Covid 19 regulations. In such an environment, activists get arrested for staging demonstrations against theft of public funds , they are told to be flouting Covid 19 rules on gathering, citizens are told to stay at home but do not have access to food and other basic necessities .When caught outside their homes past curfew hours they get arrested while politicians go to bars and hold political rallies . In every country of the world, the difference is the geographical location but the repressive methods remain the same. The murdered Honduran activist Berta Caceres of the Lenca indigenous community in visibly shows us that state repression cannot end activism, it can multiply it, in fact Berta did not die, she multiplied and now we have activists from many parts of the world becoming conscious of issues of environmental justice and negative impacts of natural resource extractions.

[1] https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-53592411/hachalu-hundessa-s-father-he-died-standing-for-his-people

[2] https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/news/2020/07/more-than-50-activists-arrested-as-police-break-saba-saba-march-in-nairobi/

[3] https://citizentv.co.ke/news/kenyan-journalist-yassin-juma-arrested-in-ethiopia-337715/

[4] Huduma is a Kiswahili word meaning service

https://www.voanews.com/covid-19-pandemic/kenya-police-fire-tear-gas-cov...

Photo Credit @Calvo Mkenya