Our girls are the real gold'

Dec 19, 2017

Story

Vangie Bago-Porogoy has survived an ambush. She lifts her shirt, showing me where the bullets pierced through skin. The scars are like bleached centipedes encrusted on her dark brown flesh.

“Some people want me dead,” she tells me. “And they could be my own kin.”

Vangie belongs to the vanishing Mamanwa tribe, who number only around 55,000. In northeastern Mindanao, the Mamanwa are forest dwellers who survive by relying on swidden farming, hunting wild animals and gathering bamboo, wild honey and firewood.

“We cannot let our children remain illiterate. With the forests soon gone, they have to find jobs and they cannot find good jobs if they are unschooled,” Vangie recalls how she tried to persuade the village assembly. “We must send every girl to school, make sure they stay in school.”

About 300 families of Vangie’s clan have resettled elsewhere as their 20,000-hectare mountain territory became a mining site. Recently, the company extracting gold and nickel from their ancestral land has paid them royalty, amounting to PhilP51-million (about US$12M).

“I disagreed on how this common fund would be spent,” she reveals. She is convinced her dissent explains the attempt on her life.

How would her impoverished clan want to spend that instant bonanza? Most wanted to divide the funds among themselves but Vangie, 28, the village’s documents-keeper, asserted instead that the fund be allotted for their children’s schooling, health and nutrition, aside from providing houses for the ageing elders.

As the Mamanwa are matrilineal, Vangie prefers educating girls. “The girls, they are the real gold. They are our reliable savings bank,” she says. Even as public primary school is free, few Mamanwa children enroll and those who do, drop out early. Girls endure longer, finishing the elementary grades till they get married, usually still in their teens.

Vangie waited till she turned 20 to get married. “That’s already considered very old in our culture,” she recalls. She was half-way through high school then, and now she dreams of school again and getting a diploma.

She lets out a big laugh, saying, “Can you imagine me? I’ll be my eldest child’s classmate!”

RESONANCES AND MEMORIES

Vangie’s zeal brings my mind back to schoolgirls Maricel and Cheska Montenegro, both aged 10. The cousins missed classes to join the protest rally against the logging corporation that fell trees on another Mamanwa ancestral forest.

It was drizzling but the people stood their ground. Shivering in the slight rain, Cheska was clutching her pencils. I asked her why she wasn’t in class and she answered, “Because I want to be a teacher. If we keep our forests, my father can gather firewood and wild honey and he will have enough money to send me to school.”

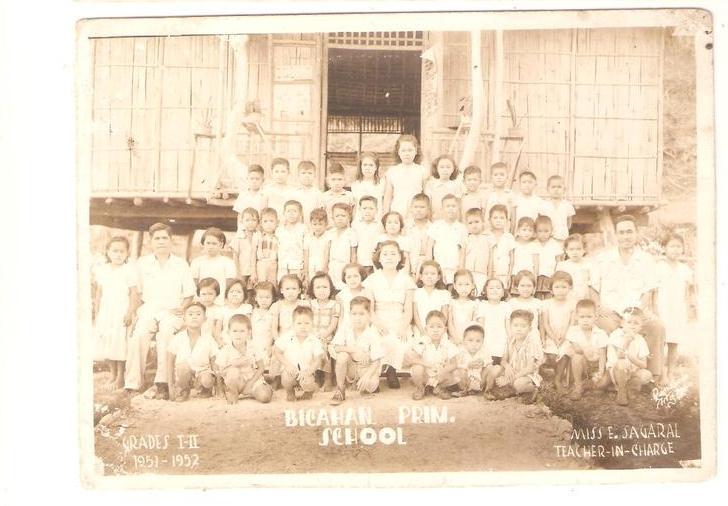

The phrase, ‘girls-as-the-genuine-gold’, reverberates too, flashing back memories of my aunt, Tia Yaying. In a circa 1952 photograph, Tia the teacher sits among her clutch of 48 pupils, posing before the bamboo school hut in a village as remote as Vangie’s own.

I imagine the long hours she spent daily, walking on a forest trail to reach the school house. She was my grandparents’ golden egg that has hatched: sending to college her three siblings, including my own mother, as she taught hundreds of children in far villages.

VIABLE (RE)SOLUTIONS

Vangie sees her redemption from danger in resolving the conflict within her clan. I tell her to wager her hopes on a peace pact stipulating that the clan invest their windfall on the next generation.

They can create alternative, safe, girl-friendly virtual classrooms. A community-managed digital or internet radio can be its hub, exploring the Mamanwa’s orality, their affinity to the Spoken Word. They can hold classes-on-air and online, linked by computers and mobile phones.

Beyond functional literacy, I suggest further a girl-oriented education, one that brings about authentic empowerment. They can build a web-based Women’s School of Living Traditions, nurturing their own heritage of songs, rituals, epics, crafts, games, genealogy; preserving in their mother tongue the names and uses of forest trees, medicinal herbs, wild animals. Online, they can discuss about rights, family planning and domestic violence. They can harness the interactive technology to network with other women Indigenous Peoples worldwide.

But I have to concede that it will take more than just the Mamanwa villagers alone to educate their children. It will take a glocal community – a confluence of government agencies, churches, NGOs and foundations working together with them. It will need dedicated teachers like Tia Yaying who would dare teach in isolated villages. It will take highly motivated children like the Montenegro cousins. Certainly, it will require a resident champion like Vangie Bago-Porogoy to shine the golden lantern of learning within the heartland of her own people’s imagination.