The Lumad map the hurts of body, mind and spirit

May 28, 2019

Story

''When we women offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all maps change. There are new mountains.'' --Ursula Le Guin, as quoted by Rebecca Solnit in ''Silence and Powerlessness Go Hand in Hand-- Women's Voices Must be Heard,'' in The UK Guardian, March 8, 2017

Rebecca Solnit's recent recollection of Ursula LeGuin's words at a commencement ceremony way back in 1986 prompted my own recollection of the braided stories of an evacuee from the remote mountain village of Kamansi, Lagonglong in Misamis Oriental:

As leader of the evacuees, the pressure for her to stand for her tribe must have been tremendous. “Ït felt like my entire body ached all over, and my head throbbed with pain, and I was anxious all the time. My one-year-old kept crying but no milk came from my breast,” said Sareza Ocampo, one of the hundreds displaced by protracted militarization in Misamis Oriental in the Philippines.

When the other breastfeeding mothers among them could not produce milk for their infants and medicines for the asthmatic and the feverish ran out, at least a dozen of the lumad women evacuees cut their hair and sold the long strands to a wigmaker so they could buy milk and analgesics, recalled the spokesperson of Tagtabulon, the Higaonon grassroots organization.

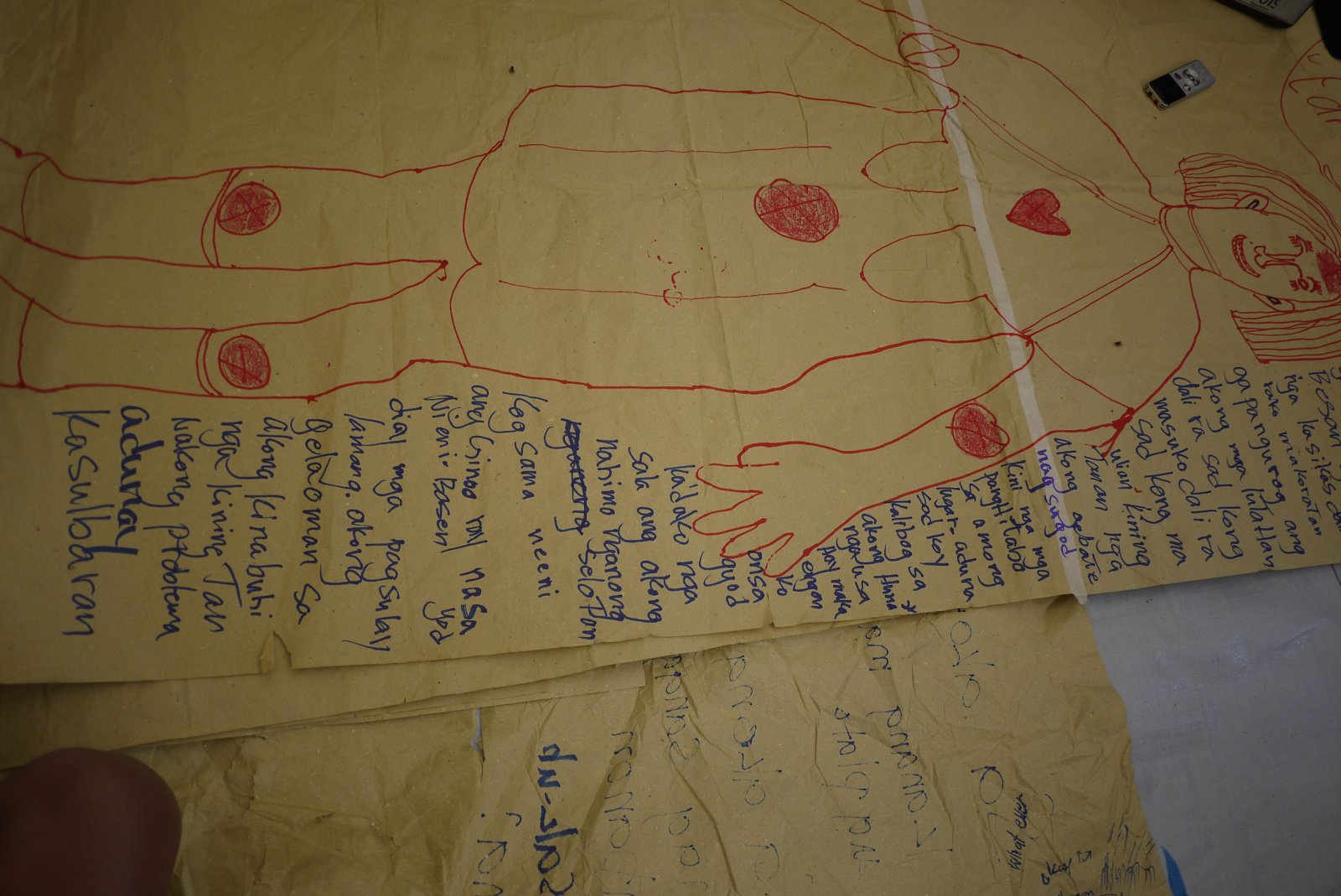

But Sareza's story began to find shape not in words or speech – its origins were bold red crayola orbs over the chest and head of a human figure on a large sheet of paper, a representation of her own body.

Like the dozen of participants of the workshop, the contours of her body were earlier traced by her buddy as she lay prostrate over a sheet of paper. Sareza in turn traced her buddy's body, rendering her shape in thick blue ink over the turmeric rind-colored paper.

Sakit, sakit-sakit, sakit kaayo

Then, they were instructed by the facilitator to mark the figure where they hurt while they were fleeing and while at the evacuation camps. Where do you hurt? What pains did you feel, which part of your body keeps on hurting until now? What is the intensity of the pain? ''Sakit,sakit-sakit, sakit kaayo'' (painful, mildly painful, excruciatingly painful)

These were the 'selfie trauma maps' of the women ''lumad-bakwit'', indigenous peoples (IPs) who were also internally displaced persons (IDPs). These are among the portable tools, and the stories that emanated from them were part of the process towards storytelling and facts-gathering in a participatory study into the impacts of armed conflict and displacement among women and girls in a group of indigenous peoples called Higaonon in Northern Mindanao in 2015. It was also, in a way, a creative speak-out for these women experiencing the trauma of displacement caused by armed conflict.

On that year the process took place, a spate of unprecedented displacements of IPs took place on Mindanao. The UNCHR took note of this trend as it reported that the situation of IDPs who are IPs deteriorated in 2015. The theatres of violence involved the government's military forces, the communist rebels and paramilitary groups as key actors. From an annual average of 400 displaced IP families (estimated 2,000 persons) previously, 2015 saw some 3,198 families (estimated 17,035persons). The UNCHR further noted that there were cases of extra-judicial killings and paramilitary attacks.

About thirty women who belonged to two groups of IDPs joined the study. The first group of women were from a village in Cabanglasan, Bukidnon province. They were mostly farmers fleeing from paramilitary groups that have killed their leaders and harassed the villagers, while the second group from which Sareza belonged, were resisting the militarization that periodically engulfed their mountain village as soldiers came in hordes looking for rebels.

Rosella Cahanggan, on the other hand, recalled her experiences that made her place red smears all over her body map. ''We were ambushed then as we walked towards the village from the farm; and my head ached because I did not know what to do, the explosions were everywhere, and my chest felt painful because we were running for our lives, my children and I, five of them,'' she said.

''We were shot at, bullets were raining on us, and my children were shouting but my heart was bursting as we ran, I was carrying my child and my arms were aching, my thighs were also painful as we could not control our feet from running because of fear;

On staying at an open camp by the park, Rosella said that ''from the waist to my shoulders at my back are numb now because we are always lying down and the ground is cold. My spine and shoulders throb with pain on most nights . A single loud sound and I and I feel uneasy and fearful.''

Previous to working with the indigenous women, I learned the use of body-mapping from Prof. Al Fuertes of George Mason University, as he used these as jump-off points to storytelling in dyads, then in circles of five or more in trauma healing courses that I had attended. Fuertes favors storytelling in groups for trauma healing rather than the one-on-one sessions of psycho-therapy. ''More listeners means more people carrying the heavy load of emotions and pain,'' he explained. ''The negative vibes gets dissipated but the the positive energy that comes from the experience is shared,'' he added. He also says that storytelling is suited to the indigenous cultures particularly because of its traditions of orality.

Dr. Fuertes says that ''storytelling can be an effective tool in transforming the negative energy of trauma into something positive and constructive... For survivors of armed conflict, for example, including those who go through the cycle of silence in reaction to deep traumatization, the coming out into the open through storytelling is empowering and affirming, enabling them to redefine their sense of identity given their new normalcy.''

i held the sessions, bearing in mind what another academic on forced migration, David Parkin, who had observed in 2002, that ''when people flee from the threat of death and total dispossession, the things and stories they carry with them may be all that remains of their distinctive personhood to provide for future continuity.

''Enabling displaced people to retain all that remains of their distinctive personhood may be vital for their future, their health, for holding together as a community, and for maintaining or restoring their dignity after the trauma of exodus and exile.''

When Sareza and the rest of the women stood up to explain the markings on their body maps, they opened up new spaces for the process of healing for themselves and contributed to their community's resilience.

A synthesis of their stories showed that most of them experienced aches in their head, chest,abdomen and feet. They felt hunger pangs and palpitations of the heart. These feelings and sensations are still considered as normal responses to the pressures and tensions of crisis that would last for a month or so. What was worrisome was that at that time, one group, that of Rosella's was going through a crisis for more than four months. Such circumstances could be the breeding ground for mental health crises like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

They were also dealing with the everyday dark stew of anger, disillusionment, despair, fatigue, and longings of withdrawal and solitude; and yet, alternately, they were also brewing hopefulness, generosity, prayer, courage, gratitude and the full resolve to resist the militarization of their land.

Elenita, the matriarch of her family said, ''There is no room for hate or fear in my heart. In order to seek justice for the murder of my son, I have to be strong and healthy,'' as she seeks for justice for her murdered son,who headed the farmers cooperative. She believed that the paramilitary killed him.

Sareza's group had already resettled at their village at the time of the speak-out, and most were returning to the routines of mountain farm life. But yet, since then, two occasions of displacement have befallen upon them in the last year and this year.

The study is under the auspices of the Mindanao Interfaith Institute of Lumad Studies, and aims to document the effects of long-standing conflicts on the mental health and psycho-social functioning of women and girls in indigenous communities in Mindanao since data on this aspect of their lives in the context of war have been scant and scarce. Yet, most lumad communities and ancestral domains in Mindanao have been sites of militarization and development aggression in recent decades.

According to MIILS, because of their potent roles in peace building and conflict resolution, lumad women’s health and well-being must be given priority focus in the healing process consequent to post-conflict peace building.

It is hoped that such data will contribute to the body of knowledge needed to implement, on the national and local levels, such global instruments as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UN Security Council Resolution 1325, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Humanitarian Law, and the Beijing Platform for Action that all emphasize the need to address and respond to the impact of armed conflict on women and girls, thus ensuring their individual and collective survival, recovery and empowerment in their communities.

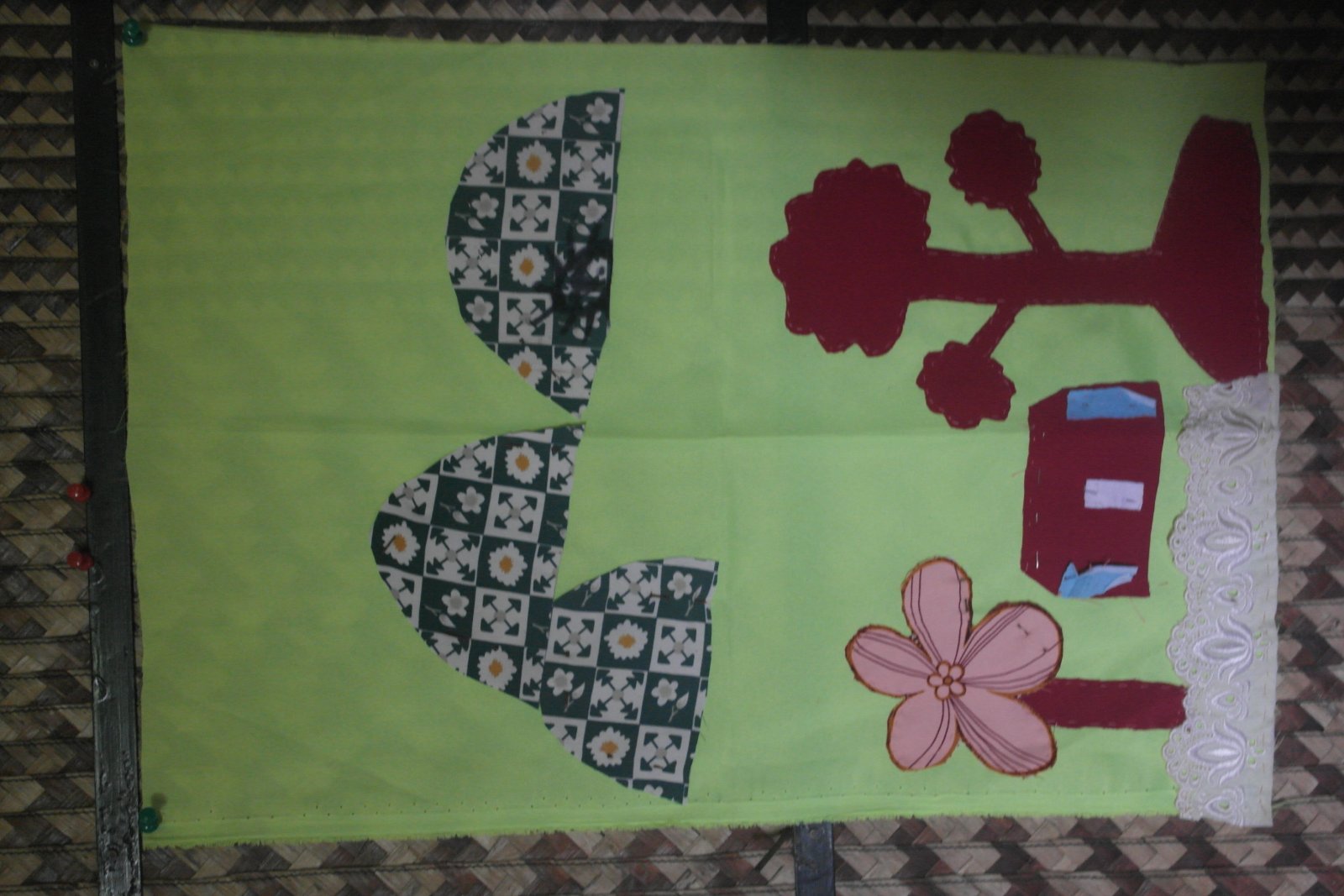

Pat(c)hwork of hopes

Later in the succeeding sessions, the women were given a heap of random pieces of textiles taken cut out of worn-out clothes, pairs of scissors, spools of threads, and each stitched together a patchwork of their hopes. The questions that guided them: What does the future hold for you? What do you bring to the future?

Most of the participants came up with a stitchery of dwellings and farms, chapels and schoolhouses, features of the safe homeland they wish to return to.

Sareza's patchwork was a hopeful cartography that's reckless bricolage of red-- against a backcloth of lemon green, a squat red house with a pink door and blue windows takes center stage even as it is dwarfed by a leviathan vermillion tree and an enormous orange bloom; a frieze of white cabbages (of embossed lace) in the foreground. And, yes, literally, a trio of new mountains.