silence-rape Protect them, stand for them- A published review in Women News Network by Jack David Eller

Jan 21, 2015

Story

Another man says that he mistreats women “because God said that man is superior to woman. The man must command, must give orders and must do whatever he wants to a woman.”

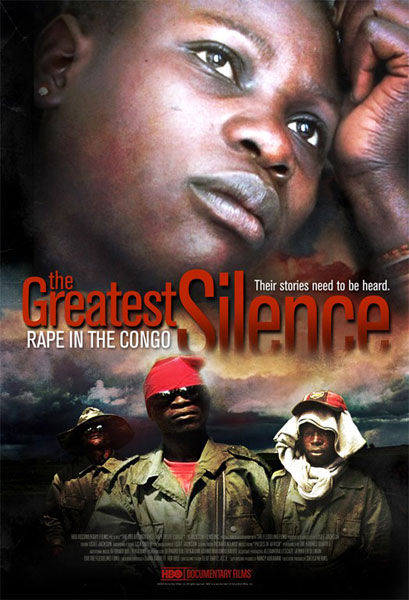

FILM: The Greatest Silence – Rape in the Congo

Jack David Eller – Women News Network – WNN Reviews

This profound and troubling film explores the use of rape as a weapon of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the human toll it takes on women, children, families, and the society.

Filmmaker Lisa Jackson, a woman from the Anishinaabe aboriginal tribe of south Ontario, Canada, leads us first to Bukavu, near the Rwanda border on Lake Kivu, where a non-profit organization called Women for Women International works with victims. Jackson’s interest in the subject is more than academic, since, as she admits to the audience and the Congolese women, she herself was gang-raped at age 25.

It is particularly stunning to see how the women of the Congo found it hard to believe that such violence could occur in America, assuming that there must be a war going in on in our country too. Throughout this film, various women tell their personal stories of rape; their shame and guilt.

Rape isFILM Poster: The Greatest Silence - Rape in the Congo not unique to Congo. The physical damage to women can be extreme and permanent. This rape is accentuated by psychological and social harm. The Congolese Minister of Women’s Affairs (a woman too) explains that “When a woman becomes a victim of sexual violence, she finds herself alone. . . She is ashamed to go home, even to her own family, because even her own husband will reject her.”

After a brief introduction to the history of the colonialism, independence, and the Mobutu regime of the country we learn of the savage civil war since 1997, where Ugandan, Rwandan, and Burundian paramilitary groups swarm through the jungles and hillsides. Of these militias, the Rwandan/Hutu paramilitaries have been the worst.

Whether they know it or not, they “maintain the chaos necessary to help foreigners loot Congo’s resources.” The country, being rich in vital natural resources such as coltan, an unfamiliar substance but one used in all cell phones and , happens to hold 80% of the world reserves of the material.

“The Greatest Silence – Rape in the Congo,” claims that $1 million worth is stolen every day. The war and its impact on women has been so great that the United Nations has sent a peacekeeping force into the country. One peacekeeper calls the Congo the worst environment for women that he has seen.

In order to document these conditions, Jackson goes into a dangerous rural areas with a U.N. escort, where she witnesses local soldiers extorting the very villagers they are supposedly protecting. Tragically, 19 U.N. peacekeepers have been implicated in sexual abuse too.

Not surprisingly, few options exist for women forced from their homes. One of the few is a tile-making business operated by Women for Women. The film also takes us to Panzi Hospital, a facility for rape survivors, where they are treated for common rape injuries like fistula, rips in the vagina and its wall with the bladder.

Up to thirty percent of the victims contract HIV. These victims range in age from two to eighty. Outside the hospital in an open-air shelter, women wait for a bed at the hospital. Many, even after any treatment they might receive, will be incontinent and traumatized all their lives. Again we are exposed to tales not only of rape but of gratuitous torture, like holding one woman over hot coals to burn her rectum.

No investigation of rape during war would be complete without the rapists’ perspective, so Jackson travels into the conflict zone to meet the soldiers-rapists. A typical attitude is expressed by one fighter: “I rape because of the need. After that I feel I am a man.”

“I am in need. If I ask and she says no, I will take her by force,” he continues. Another man says that he mistreats women “because God said that man is superior to woman. The man must command, must give orders and must do whatever he wants to a woman.”

Part of the problem, as in so many settings, is the lack of any police response to the crimes. Jackson visits the one-room shack that is the ‘office’ of the one-woman special-victims unit. In Congo there is no police for sex crimes.

In a too-common outcome, a young rape victim (raped by a policeman, no less) sees her perpetrator arrested, only to escape and remain at large. In a world where, as one commentator puts it, “Violence has become a lifestyle,” there are many locations for the violence and its aftermath. We see a refugee camp of more than 100 women who have been raped and held as sex slaves.

Jackson also finds a Catholic church which is the only refuge for many remote villagers; there, a support group is organized by an African nun.

There are some activists in this society, but their voices are small and weak.

Meanwhile, the policewoman visits a village to investigate a case of a 4-year-old girl who was raped. Children produced by rape are often condemned to centers like the one we meet next—some abandoned, all stigmatized.

The final minutes of the film throw many other images at the viewer. Congolese citizens rightfully worry for the next generation of their country; a generation that is getting little or no education; that has been stamped by the violence it has experienced.

In her interview of more soldier-rapists, Jackson finds that they are often motivated by a particular local superstition that sex will help protect them in battle.

“We raped them because of our belief in the magic potion,” says one of the soldiers. A few of the men even insist that sex is a sort of patriotic act for the women, a way to empower their fighting men. However, the women seeking help in a small local charity do not seem very patriotically inspired.

The film closes with a number of cameos of women in their suffering and various depictions of the men and women who care for and about them. As the policewoman, who has probably never read the regional language, Olujic, summarizes it, “He who rapes a woman rapes a whole nation.”

It is no wonder that,“The Greatest Silence,” was the 2008 winner of the Sundance Film Festival special jury prize for a documentary.

It is a really strong piece of work and Jackson is a remarkably brave filmmaker to go where she went, and ask the questions that she asked. The portraits of the women in pain, as well as the soldier-rapists who appear indifferent to that pain, are almost too much. HBO is to be commended as well for producing the film.

In the first week of February 2011, one would like to think that the events of this film are history (if only 4-year-old history). However, less than a month ago the BBC reported that, “An army commander in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo has been accused of leading the recent mass rape of at least 50 women.