Why are rounded pebbles so common? A quick glance on natural shapes, and their durability.

Jan 21, 2015

Story

I'm quite sure you noticed it: on average, rounded pebbles are more common than sharp-edged ones.

OK, you're quite right! My statement is not so universal, and I can tell it in my area (a temperate flatland not very far away from the Alps).

Nonetheless, the vast larger amount of rounded pebbles amazed me since childhood.

The reason of this, and its consequences, sounded me thrilling and inspiring in the same time.

Why, then, so many rounded pebbles?

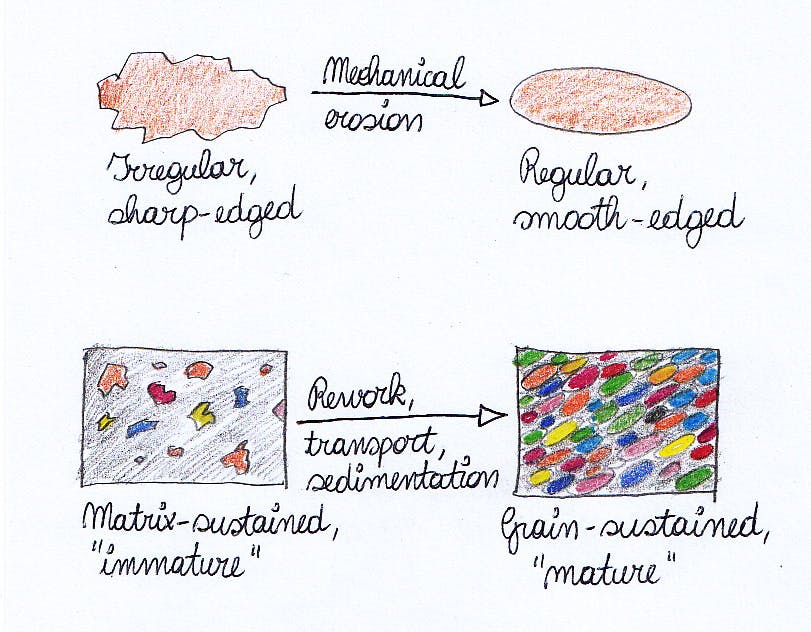

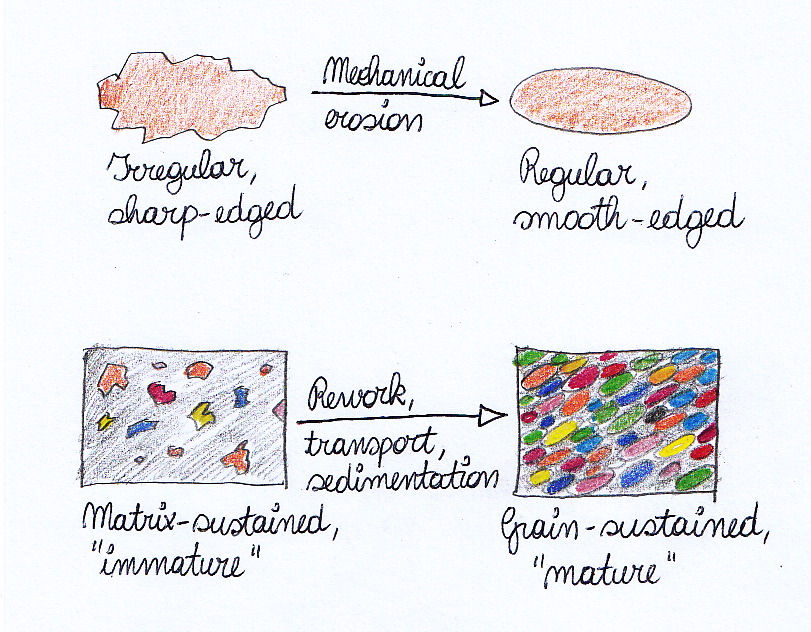

When rocks disintegrate, under the effect of physical erosion like freezing-thawing, the resulting stones are mostly sharp-edged and very irregular. They may stay there, possibly incorporated in some finer grained sediment, and diagenesis (that is, the process of rock formation) will "freeze" them in place, with minimal change of shape.

Or, what happens frequently, they will be transported away by some river, or marine waves. The finer-grained sediment is then washed out, and individual stones are eroded. This is an interesting step: fluvial transport, or wave rework, are not an indifferent "grinding" crushing large stones to sand particles. Rather, stones interact (more specifically, collide) and in the process all irregularities, more exposed to collisions and vulnerable, will eventually be polished out. Eventually, our sharp-edged stone will reduce to a smaller rounded edged stone, plus some sand particles.

From then on, the rounded pebble will continue to erode mechanically, but will do at a much slower rate, no sharp irregularity offering a preferential damage point.

In other words, it takes quite little to reduce a sharp stone to a rounded one, but a much longer one to make the latter into sand. Longer lived, rounded stones are then more common in sediments.

Geologists say the stone has "matured" into a nice, smooth pebble.

Now, let's take a more general standpoint. We may say that the edgy shape of "immature" stones is less durable than a smooth surface. The edgy shape has less entropy than the smooth!

- *

If you look around in Nature, you seldom find sharp edges.

But to notice it, you should be "objective". We aren't, as our perceptual system gives a higher weight to living beings (and we alive creatures are among the most edgy-shaped objects on the planet: think the many layers and organs we are build from, and the innumerable cells, all characterized by extreme chemical and geometrical gradients).

So, let's turn to "mineral" objects, and look them impassionately. Are sharp discontinuities so common?

On a first glance, mountain faces seem quite common - but if you take really all into account, you invariably find them surrounded by large pancake-shaped, rounded walls. And we have to admit: sharp edges are uncommon.

In addition, when they exist, then there is some process actively maintaining them visible. Like, for example, an active fault. Or a river cutting a very hard rock.

Stop this process, and give time a chance, and these sharp feature will soon vanish.

Of course, this process can be more evident in some places. My brother lives in the Central Alps, and when I go visiting him I always stare at the high faces covered on time to time of snow, in awe. Reflecting, I have to admit the Alps are a very young range, still evolving and lifting. So, a chance is there for sharp edges.

But move North, in Europe, until the Ercinic massifs of Central and Northern Europe... There, landscape is much different, smoother, and pancake-like. The Ercinic mountain lift has long ended, and now erosion dominates. Smooth edges are decidedly dominating. The same will be in our Alps, on some day.

- *

And technology?

As two examples, chosen at random, let's imagine the latest kind of super-powerful microprocessor, and the huge Rho-Pero exposition building north of Milan.

These two objects have very different scales, but one important thing in common: extremely sharp edges and strong gradients.

The difference is so striking, that I guess even a Venusian would distinguish artificial from natural forms.

The same could be said of most current technology, from clothes to cars to cultivated fields, to literally anything artificial.

So sharp-edged they are, that our technological products demand a continuous flow of energy to maintain them alive, in form of cleaning and repair. The very existence of shapes so far from the natural smooth surfaces and gentle gradients implies a disequilibrium, which in turn obliges to spend an immense amount of money, time and natural resources to maintain it.

The consequence of sharp edges and extreme gradients in artificial objects is their very small durability. As the sharp-edged stone, they are crushed quickly by the normal weathering processes acting on any rock. And, they fail frequently (the sharper the surfaces, the faster the death).

- *

If smooth forms are more common in nature, why not adopting, copying them in our technology?

I don't know "why", but guess this might be a significant progress: a more lightweight technology, all functions fixed, would be automatically more reliable, durable and possibly less expensive than a sharpy thing. It might require less maintenance, and so the overall environmental impact could be much lower.

Last, and not least, I guess these objects would be beautiful, in their way.

- *

Technology "is" shapy and sharpy, however.

Form and function obviously intertwine, in so many cases.

I can't exclude they would be also with different kind of shapes, fabrics and textures. But I feel it could be quite difficult, to the untrained eyes of our minds, to figure them out.

Maybe, the apparent connection of sharp forms and functions stems from the way things are manufactured. To date, even the most sophisticated production processes operate by assembling simpler things, or removing some mass from a larger body, or making a liquid into a solid.

Whatever we do, we don't "grow" objects. And by the way, we limit the range of possible forms to a very tiny subset. An optimal one?

"Growing" things, as we find in the biosphere, have inherently complex three-dimensional shapes. They exhibit large gradients, as I mentioned. But they do in a different way than artificial things.

- *

A smooth surface desn't cut very effectively.

There are cases, in which a sharp blade is more than a necessity (I'm saying this by direct experience after having tries to skin a mature peach with a poorly sharpened knife: a total liquid disaster (not preventing me from eating the peach, of course).

In other instances, the usefulness of a sharp edge is much less clear. Is a sharpy car frame aerodynamical enough?

If we consider external surfaces only, then sometimes a smooth form emerges from trial-and-error, or computer simulation, especially when some tight interaction with a hard medium is in progress. Like airplanes designed for high speed.

The human body, as many other animals, is basically streamlined too. Not as dolphins', sure, but remarkably. Why?

And why, in any population, some individuals are more streamlined than others?

Is it the consequence of subcutaneous fat distribution, and its normal variability? Or, has it some unknown direct adaptive meanings?

- *

I'd appreciate a lot a technology more akin to nature, and less heavy to the environment. Meanwhile, I wonder whether big investments would be ever placed into it.

It's hard to, but I have to admit to myself that many products of technology have not been developed out some documented, or potential, necessity.

A specific example, in my opinion, is the Messina Strait Bridge, now under design. The most important motivation I see behind of it is celebrating the prestige of a political class, and maybe a single party. Once made, it will stand, and little doubt it will not pass unobserved.

Many other things have been built outside any perceivable necessity, but providing some tangible sign of the persistence of an ego long after his death.

It is not easy for me to buy into this kind of insecurity. I feel having the opposite problem, of leaving not too much traces after my passage (the ones which will remain will mostly be in the form of environmental impact, and resource deprivation to future people and other beings). But, apparently, this is>/em> a motivation. An illogical one, maybe. And perhaps, more conductive to shapes so that no one in the future will mismatch for a natural accident.

This is, I feel, a big, open question.

- *

Dear friends, I'd like to hear from you about.

The problem is, despite its appearance, deeply physical and mathematical. So, not outside our reach!

I end here, wishing you all any happiness possible (and doing this from a very shapy computer ;-) ).

Mauri