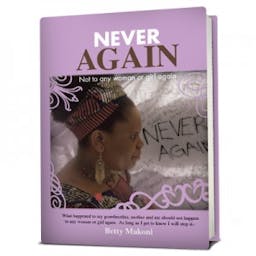

Excerpts from Betty Makoni`s Autobiography:Education for girls is lifetime investment

Jan 21, 2015

Story

Chapter 43: In the rubbles lay a genius-Esther is my story

I heard my former teacher’s voice on the phone pleading for me to come help this unfortunate girl by the name of Esther Saidi, who was at the top of her school and the whole country for grade seven. Esther had spent many days with her ailing grandmother vending and farming just to bring food to the table. The girl had survived poverty and being parentless--she had only her grandmother to turn to.

“Come help her, Betty, please. You are the last person we know who can help,” said my teacher, Mr. Tizora.

Mr. Tizora was the teacher who took us for grade seven in 1984 at Chishawasha Primary School. He had not perished in the fatal accident that killed six of our teachers and left the school devastated. He had not gone to collect his pay on the day that this happened.

I put my head down on the desk and visualized my teacher on the phone and then this unfortunate girl just waiting by his side. I wondered how many times he had called for help. There was no hotline one would call if they see a child dropped out of school because of poverty. There was no hotline to call to report children not in school needing help. My teacher said I was the last one he had to turn to. This really showed that the scholarships for girls to be in school were not available still, or if they were it was a tightly guarded secret. Funds to send a poor child to school should be as available as the air we breathe or water we drink. It is life. I don’t understand why any nation would move forward without educated girls. Nothing had changed at all and nothing would change. If anything, things were getting worse for the poor. With HIV and AIDS, which wreaked havoc and left many children parentless, what remained was survival of the fittest. No one kept a register of bereaved children. I just saw posters and fliers sympathizing with them. What I did not see are emergency vehicles rescuing them from situations of pain, poverty and neglect. How could someone set up an organization to feel pity for a poor child without doing much?

I had promised my teacher that I would come and meet the girl and assess the situation to see what I could do. I always put my head down to think before I embarked on any rescue mission. There was no money to send the girl to a girls’ school. Most of the money we had was in small grants to do awareness programs and help victims of rape. Esther was not a rape victim at all, and so she did not fit into our criteria of those receiving educational assistance. The other funds we had were from Oxfam Novib and that money was not for poor children to be reinstated in school. Rather it was money to raise awareness and change the mindsets of communities to help their children. It was for capacity building, and to be frank, and I did not understand why I ever agreed to take money that develops staff and communities and girls clubs without taking funds that would lift a girl from rubble into a good school. The budget was strict, and once signed for, you could not change it; the money was untouchable. So I kept cracking my head about how I would squeeze for some money out of the allocated budget and help this girl. Telling my school teacher I was coming was always my way of taking a journey to think strategically about what practical help I would render.

I got to Chishawasha near the seminary where priests train and that’s where Esther lived. The school was St. Josephs; it was a village school once supported by the Roman Catholic Church, but it looks like there had been a transition to a new authority. The nearest secondary school was 10 miles away. This meant children spent their whole days walking back and forth to the school. Energy was always spent in walking and not learning. That’s why sometimes children who walked 10 to 20 miles per day to school were physically in school, but due to exhaustion during lessons, fatigue, hunger, and being overworked in the morning, not many were emotionally attached to the school and education. Going to school was just a formality to have a register marked. Not many children got much from education, no wonder some girls opted out of school to get married rather than be an athlete leveling mountains and hills to school every day. It is one of those punishments the class system imposed on poor children so that they never exist.

I wondered why secondary schools were so far away. To hell with whoever designed a school system to end with primary school when school went up to University! By 2002 there were still no secondary schools close to this primary school that all the poor children could access. The two nearest top schools, even in the country, were St. Dominic's and St, Ignatius and these took children whose parents could afford it. How ironic that all these children were within walking radius of such schools and on opening days they saw buses ferrying children from elsewhere in Zimbabwe whose parents were in the working class and could afford to send their children to school. They always stood by the road to be spectators as well-to-do families took educational reigns. This is where I always cursed the class system. A lot of times you are close to an opportunity and you see it every day, and then the door is just closed-- permanently banged against you. It is a situation where you stand in a well with cold water whilst being deadly thirsty and you cannot be allowed to drink a drop of the water.

What pained me most was the absence of a University or small college in the area. I left Chishawasha in 1989 and no matter how many times I was there nothing like a University or vocational skills center had been built. I heard there were town planners and other council staff for the development of the area, and all of them were highly respected and educated men and women. It was clear they had not done much, save to have tea at 10 a.m. and lunch at one p.m. They had taken up offices built before independence, and the only development they had done was to paint the offices and buy new furniture, and of course put big capital letters on white titles of their posts. The dusty road had become dustier and more damaged. The tarred road still ended in the nearby posh suburb of Chisipite and the Grange area. It then threw the villagers and anyone who came to them into rubbles and that’s where all of the poor had taken to lead lives that were such a short cut to getting employment for rich people in nearby suburbs. No matter what good grades one obtained at grade seven, they graduated into someone’s kitchen or garden and that’s where their life started and ended. I realized that the class system deliberately deprived the poor and that this resulted in informal slavery where they worked for the rich black families as nannies and garden boys with little or no pay. The nannies and garden boys married each other and failed to send their children to school and then the children took over lowly paid jobs as nannies and garden boys when their parents retired with no pension or income. This was a vicious cycle of poverty that could have been addressed by a good policy on remuneration and pension schemes. I think some of the poor children who were clever enough opted to be priests as that was the easiest entry to a better life, as the seminary took just those who wanted to resign from earthly life and serve God. I don’t understand why the church did not add a vocational training college for poor rural children in the area but opted for a seminary. But who was I to question anyone anyway?

I finally arrived at the school and met Mr. Tizora. He had not changed at all. He was just a teacher risen from a mission to becoming school head at an upper top primary school. His wife, too, had not changed–she was beautiful and very natural. She was light in complexion and one of the well-made teacher’s wives of all times. I did not know her story at all’ all I knew is that she had been a wife all her life.

Mr. Tizora said he would ferry me to where Esther lived and then we headed off there. When I got to the dilapidated huts, two of which had been refurbished by small trainee priests at the seminary, I got the shock of my life to see that people could live in such houses in a country where some black rich people had bullet-proof houses. First I did not understand how such an old grandmother had survived without an income and how she had lived with no one to help her. If she was in UK or the Western world she would have been placed under care. It looks she had lost some of her children. She stretched her hand to greet me, and it was an overworked hand with fingers that spoke of hard work and pain. The gesture to greet me first, even if in years she was older, immediately struck my heart and confirmed to me poverty had reduced her life to that of a servant-like bow down in humility. I knelt down immediately and refused to take any such servant-like gestures, as they would make me break down. The poor girl in me is immediately evoked and I refuse to see what I used to see. I threw both my hands with a humble bow and knelt close to her. She touched my heart. I held my tears tight to my heart. I did not want them to come out as breaking down in such situations left things worse.

I needed no one to share the story more. The rest of the story I told from my own. I had no capacity to take in pain by asking someone to share the story which I could tell on my own. It was urgent on my part when confronted with girls like her for me to suppress pain within for the sake of moving quickly to action. Her grandmother had the whole story written in her tearful eyes. She had the story written on her chapped and overworked hands. Her granddaughter’s story was written on the falling huts where she lived all these years and remained loyal to education even if it meant being in class on an empty stomach. It was written on the rain that intruded into the poor hut and caused potholes inside. It was further confirmed as a story of abject poverty by the absence of food on the cooking stand. The grandmother had parented her children with the hope she would take rest in her old age, but now I saw a grandmother resigned? to be a mother and father at once.

Her granddaughter had scored four units at grade seven and she was one of the top girls in the country. I wondered if she knew what this meant. I liked her remote understanding of what education is, but my tears fell inside for her because she did not know what her daughter would be. She kept saying I should take her, even if it meant working in my house. I wanted her to be proud she had produced the most intelligent girl from the falling hut and that she had the brains of her granddaughter. To me, this was a story of a girl who studied in the dark with no book or tutor and still managed to score highly: That spoke volumes of resilience. Many children in big-story houses nearby this village had nannies, garden boys, bedrooms with ensuites, teachers, schools with under-utilised books, excess school fees, filthy rich parents, private tutors, swimming pools, holidays, drivers who dropped them to school daily, and just owned everything in the country had scored only 36 points and yet they would go to best schools in the country.

I told her I would take her daughter to work out if she can go to St. Dominic's. That was my old school and I knew the school head would not turn us down.

I found Esther clinging to me the whole journey. She kept calling me, “Mama.” I felt tears in my heart. Every time I asked myself how many times they would flow before I am satisfied I have tried my level best? Now I had taken Esther and left many other girls. She evoked my motherhood. I had failed to have daughters and I really needed her to be my daughter. That thought I quickly erased for I wanted education for her. I wanted to keep that professional distance.

When we got to my place, I told Esther I would send her to St. Dominic's school for girls. She lived close to the school–20 kilometres away, and knew about the school from the outside. She knew this was a no-go area for poor girls in her village. She was shocked she could be allowed there I told her that, yes, she would be there. I was almost in tears again when she kept bowing down to say thank you. I thought poverty can make people do certain things one would think insane. A girl of her age in rich families is always reminded to clap hands and to be grateful. With Esther it was automatic. Even when you said something kind, she responded with, “Thank you, “Mama.”

Esther returns to her village to say goodbye to her grandmother. I got her a family who adopted her and offered a scholarship at a Top US University. She wrote to say thank you and all I told her that the best way to say thank is to continue being kind and helpful to other girls like her. My hope is that despite comfort they enjoy now, girls like Esther can always make a physical and emotional return to their past and as a reminder of what needs to be done in order to pull out many other unfortunate girl from such rubbles.

I took her to buy uniforms and when she tried them, I saw myself in her: a Santa girl destined for greater heights. By the day when we were at our best, we prided ourselves with the “Santa” title, as it meant everything great, beautiful, and intelligent. I kept seeing Esther making a big breakthrough into another class and this made me tear up. She waved goodbye and left for school. I was moved to see her get into our twin cab and drive off to start a new life and journey. To be frank, in moments where I assisted girls, I did not so much worry about money coming out of our reserve fund. I worried more about a girl going to school and obtaining education. I also made sure as long one could produce receipts to our accountant and show funds were spent on girls that everything would be fine.

It looked like Esther was out of it. She was out of a place where children ended in primary school and were recycled to work as housemaids and garden boys for those in nearby posh suburbs. What was apparent were big houses in the hill like nearby Chisipite area and that is ten years after independence. There was no single vocational training center.

(Esther Saidi is completing her degree Economics and Accounts at Top University in Washington DC)